It is the mother of all games. England-Scotland is the oldest footballing rivalry in the world, the first encounter ending in a scoreless draw in Glasgow in 1872. The fixture was the sporting culmination of the historical antagonism between the two British nations and the two will meet again on Friday at the Wembley Stadium in London for a 2018 World Cup qualifier.

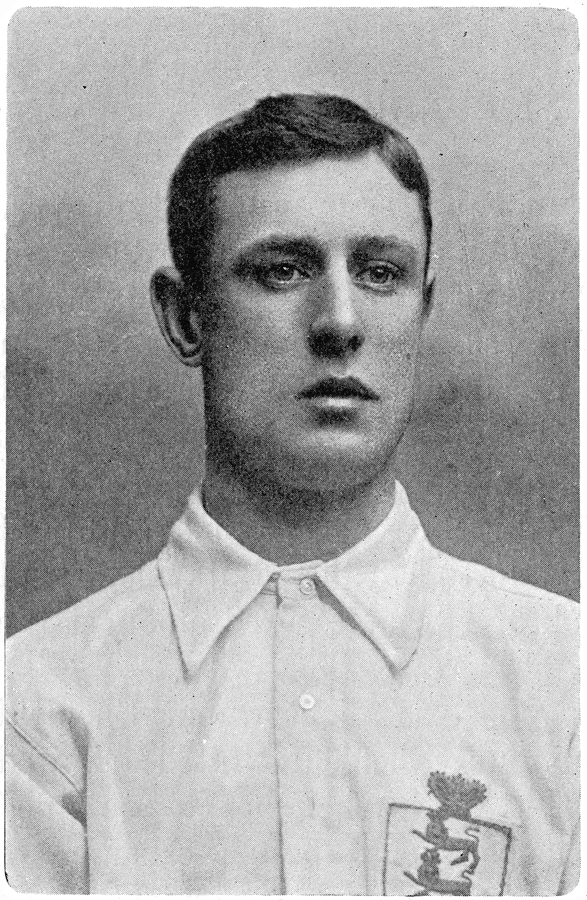

One of the early heroes of this historical rivalry was Fred Spiksley. In 1893, he scored the first hat-trick for England against Scotland. The winger was a colourful character – a flawed hero, who had an extraordinary life through football. Scroll spoke to Mark Metcalf, co-author of the book Flying Over An Olive Grove – The Remarkable Story of Fred Spiksley, about the idiosyncratic player and his very interesting life.

“Spiksley’s hat-trick, and Billy Bassett’s skill forced the Scots to professionalise their game after that match in 1893,” said Metcalf. “When England turned professional, you can see that they dominated Scotland – from 1888 until 1893, England lost just one game against their neighbours. That 5-2 [in 1893] defeat was crucial to Scotland’s development. They took the decision to allow professionalism almost the same evening after a discussion between the Scottish Football Association and the players. The English players were celebrating with a beer while the Scottish were in an emergency meeting. The way Spiksley and Bassett destroyed that Scottish defence was a catalyst.”

Fred Spiksley was born in 1870 at a unique moment in the history of the beautiful game. Why do you say so?

It was the period when professional football was born. The game represented an opportunity for the working class to get away from the harsh industrial labour that they would face for the rest of their lives. His wages were not really better than those of coal miners, but he had a better life – fitter, and without the difficult and horrible labour.

At his peak at Wednesday [the precursor of the current football club Sheffield Wednesday], he earned £3.50 in the 1890’s – a coal miner would have earned about 25 shillings. The steel industry and the cutlery industry were the cornerstones of Sheffield – he earned double the wages of a 60-hours-a-week skilled worker.

Spiksley became a star, but he was not the archetypical player, who would go to the pub to enjoy both a pint and his stardom. He would have become a compositor were it not for football. He completed his apprenticeship at a newspaper in Gainsborough.

He began his career at Trinity in Gainsborough?

It is a small town in Lincolnshire. Currently, they are in the sixth tier of English football. Their gates would not be too dissimilar from Spiksley’s time – 600 or 700 fans. That is a significant number, given the number of people who live in the area. Traditionally, Burnley, Sunderland and Middlesbrough are top when it comes to this statistic.

His parents had an agricultural background. Lincolnshire is a farmland area, where certain crops grow. Britain had the industrial revolution and Spiksley’s grandfather and father were forced to work for industrial establishments. They went to work for various manufacturers. It was a time of innovation and great investments.

Spiksley left his apprenticeship to go watch horse racing and gamble. His father was livid. There were no trade unions and he got dismissed on the spot. Sheffield was bigger and it was easier to form trade unions. The lace workers in Nottingham became unionised and they demanded Saturday afternoon off. It was a fight for leisure time in which they would play or watch football.

What role did Ireland’s John Madden, one of Spiksley’s early coaches, have on his football development?

There were a number of important people in his career. Charlie Booth was his sprint coach and taught him how to use his pace. He had already developed his skills and had control of the ball, but Madden refined those skills, but also taught him that football is a team game and that first and foremost, you have to utilise your skills for the benefit of the team. Today, you have a number of players who are better than the team. Lionel Messi is the obvious example.

In the 1980’s, that was Diego Maradona. Spiksley played out wide and therefore he could not dominate the game like Messi and Maradona, but he could win you games. Madden made him to understand that you have to pass the ball and understand your teammates.

So, Spiksley gained prominence at Wednesday?

He did. Amateurs were still the dominant force. England would be captained in the main by an amateur. John Goodall was the first great working class footballer. He did not play in the 5-2 game. He played for Preston North End. Goodall played as a No. 10. Spiksley was more of a winner.

Football turned professional in 1885. Did Spiksley realise how momentous this was?

No, he did not even know when he began his apprenticeship, that, at the same time, he had signed a professional contract for Gainsborough Trinity. One of the players had to tell him to go and collect his money. He was deeply upset that they had not paid him. He demanded a bigger wage and got one. But he must have been clever – he was able to write and he had an understanding of mathematics.

Spiksley must have realised how lucky he was – he was the first player to get a contract for three years.

Playing for Wednesday, he got the call up for England and the blue cap.

Caps were brought in to distinguish the goalkeeper. It was decided that international players would get a cap of the opposing team. Scotland’s traditional colors are blue, so Spiksley got a blue cap. With respect for Wales and Ireland, Scotland were far stronger – to play against Scotland was the pinnacle of your football career.

In the 1890’s, playing Scotland was [priority] number one, winning the FA Cup number two and winning the league number three.

That 5-2 game was special in many ways…

The Scots allowed professionalisation afterward, but it was the first hat-trick for England against Scotland. In England, it was the largest crowd as well for the game. It was also the first time royalty attended an international fixture. They had been to Burnley at Turf Moor in 1887.

Prince Albert had gone to some games of the Corinthians, an elite amateur club. For royalty to attend England-Scotland made it a big social occasion. Football was becoming important across British society.

After his playing days, Spiksley went into a coaching career?

He was not the best manager, because he always wanted to disappear from work to go and watch the horse racing and gamble. That was his number one addiction and that was what he was thinking about. He was better in teaching skills. He struggled to find managerial positions. He was offered a job at Watford once, as long as he committed to not going to the races.

“Well gentlemen, I would very much like to take up this position, but what I do in my private life is no business of my employers,” said Spiksley. He turned it down. With that attitude, no one wanted to employ him. Overseas, he took up a position in Sweden. He revolutionised Swedish football – he taught the players how to move and how to pass. He did it with the national team of Sweden, but he coached all over the country. He learned Swedish, even if he was there for just a matter of months, to convey his ideas. He was clever.

From Sweden he moved down to Germany. In 1914, the war started and like all other British citizens, he was thrown into jail in Nuremberg. Spiksley was one of the few to trick his way out. He pulled a little stunt.

How?

He had a dodgy knee. The Germans incarcerated people who they believed would be fit enough to fight. He had to demonstrate that he was not. Overnight he boiled lots of water and he poured it onto his knee. That pulled his knee out its joints. He could not walk when he went to see the doctor. He must have been in serious agony. Painful, but ingenious! He was allowed to go home.

He went to the United States and was successful in the Pennsylvania area. In 1927, he returned to Nurenberg as coach. He was successful, but he was not liked. The players did not understand how good a player he had been. Nurenberg was the big team in Germany, but the club was beginning to struggle. The players may have been big-headed. Spiksley might have been big-headed.

As a person, he had two defining characteristics – his gambling addiction and his entrepreneurial sense. Where did those two traits come from?

Spiksley and his family lived in Gainsborough, a place where people liked to “turn a shilling”. His dad, when offered the opportunity, became a pub landlord. His brother was a bookmaker. Spiksley ran an under-the-counter betting ring. He ran that often when he was out of work, and in particular, when his son had smashed his head after discovering that he had a fling with a woman in America. But also, he ran it professionally until his old age, and he did nor want the taxman to know he was earning money.

Where would you put Spiksley in the pantheon of English footballing heroes? The great Herbert Chapman certainly thought highly of him.

He won every major prize. He won both the first and second division. Spiksley played against Scotland. He played three times, won two, and drew one. He was the best player in England’s finest pre World War I forward line. He also won the FA Cup.

Spiksley had great control of the ball. He was very fast even with the ball, good in front of goal. He is the only player in English football ever to play the game with the outside of both feet. He was one of the greats of English football. Think Theo Walcott, but he was a better player with the ball and he was just as quick. He would be a better Walcott by some margin. He might have been squeezed out a bit today, because fullbacks also attack today. Spiksley’d probably play as a fullback today.

Football back then was very different – 2-2-6 or 2-3-5 formations were not uncommon and the emphasis was on individualism.

The formation back then was 2-3-5 – two full-backs, three half-backs and five forwards. There is a parallel with today’s game. The wingers would link up and knock the ball long. Spiksley scored off a long ball against Scotland. He came on the blind side and beat them for pace.

The third goal was the controversial one – all the Scottish journalists said it was offside. The game had developed very quickly in the 1880’s with Queens Park Rangers. By the 1890’s, the game has become refined, it was about passing. The centre-half was the key player. He was the one that had to score. Spiksley was unusual in that as a winger he scored so many goals.

In Spiksley’s time, England-Scotland was the pinnacle of the game. Today, both nations have regressed and the match has lost much of its cultural significance.

Today, England-Scotland is a largely uncompetitive game. Scottish football has declined significantly from the mid 1960s and 1980’s onwards. English football has a lot of money, but a lot of its money is spent on players that are not English or Scottish. So the pool to pick from for the national teams is far smaller. In the early 1980’s, Liverpool dominated European football. Every player was British until Craig Johnston came along. He was from Australia.

The national managers had more players to pick from. The game does not mean as much to the supporters anymore. England won the World Cup in 1966, and the following year the result at Wembley was England 2, Scotland 3. Scotland declared themselves the world champions! That is not going to happen again, right?